For the second year in a row, gun violence in Chicago fell. Homicides in 2018 dropped nearly 28 percent over 2016, to 561, and shootings plunged nearly 33 percent, to 2,391.

The decline is a welcome development for a city whose struggle with gun violence has been the focus of national headlines and political pronouncements, particularly from President Donald Trump.

In 2016, the city’s homicide rate reached a level not seen in two decades, and 90 percent of those deaths came by way of a gun. Seeking an explanation for the surge, observers pointed their fingers at a slew of perceived culprits, ranging from weather to fractured gang hierarchies to drops in social services funding.

Researchers at the University of Chicago Crime Lab set out to test whether those explanations were true, and published their findings in a report with the straightforward title, “Gun Violence in Chicago, 2016.”

Drawing on a meticulous examination of data, the researchers concluded that the rise in killings was a “puzzle.” Weather patterns were not abnormal. Spending on social services and public education held pretty steady. Officers were solving a smaller proportion of homicides and nonfatal shootings — a calculation known as the clearance rate — and while that may have fueled retaliatory violence, it was unlikely to have been the reason the surge began. But just because researchers couldn’t pinpoint a cause didn’t mean the city should shy away from formulating a response, the researchers wrote.

Nor did it. In February 2017, the Chicago Police Department began setting up new district offices for police and analysts from the Crime Lab to track trends, predict trouble and deploy resources accordingly. The first such offices, christened Strategic Decision Support Centers, sprung up in the neighborhoods of Englewood and Harrison. Since then, the department has expanded its use of SDSCs to 20 of the 22 police districts.

But just as the violence two years ago prompted a search for what might have caused the surge, the declines in 2017 and 2018 have yielded an array of explanations. Officials have cautioned that it’s too soon to celebrate, but to help us make sense of the numbers, I went to Max Kapustin, a research director at the Crime Lab who has been heavily involved in studying the city’s crime statistics and assisted with the effort to set up SDSCs. The interview was conducted in December, and it has been edited for length and clarity:

Brian Freskos: When you and your colleagues looked at Chicago violence in 2016, you concluded that the surge was something of an enigma. Now that more time has passed, have you been able to identify what drove that spike?

Max Kapustin: You’re right that that was essentially the line we came to. It wasn’t just merely the fact that gun violence in 2016 was higher than 2015 — that alone leaves open any number of possible explanations — but it was that violence in every single month in 2016 was so much higher relative to the same month one year before. In addition, the rise was heavily concentrated in gun crimes, but you did not see a broad increase in property crimes or drug crimes or any other sorts of crimes, so it was really just this one narrow, albeit highly important, very salient and very tragic kind of crime.

But in a lot of respects it was an unsatisfying answer when we wrote the report, and it remains unsatisfying now. There’s a lot we don’t know, and in part that’s because a lot of the factors that relate to gun violence are things that are not observable. If there are changes in conflicts between individuals who would engage in gun violence, that’s not going to be recorded anywhere. There’s no dataset you can look at.

BF: Homicides and nonfatal shootings are on track to post their second annual consecutive decline this year. Keeping in mind everything you said about the difficulties around data, is it possible to attribute these drops to anything?

MK: Yeah, I think so. If you look at certain areas where you can isolate specific interventions or changes in policy, you start to see the inklings of a story forming. One of the clearest examples is the SDSC in Englewood. Here you have an intervention that is clearly focused on reducing gun violence in a district that saw an enormous increase in 2016, and our analysis has shown that at the moment the SDSC was introduced, gun violence fell dramatically and has stayed low. Because of the amount of gun violence Englewood historically produces, that drop had an impact on citywide numbers. But you still have to ask what accounts for drops elsewhere. The impact of SDSCs in other districts is a little less clear, and there may be some other factors at work.

BF: What, in your mind, makes the SDSCs effective?

MK: The SDSCs have brought about a massive change in policing and management practices in the districts that have them. You get the folks that have the information you need in the same room, you get them to share that information, and you formulate your decisions based on that, and you do that day in, day out. This sharing of information across silos and using data to inform decision making was not happening enough at CPD prior to the SDSCs. But I don’t want to make CPD out to be noteworthy in this respect: This happens in a lot of police departments. It’s probably the exception rather than the rule that information is shared easily, and there’s still a ways to go until information is truly flowing across all these silos in CPD.

BF: Do you think that the drop in homicides and shootings is palpable for the people living in the neighborhoods most impacted by gun violence?

MK: This is verging into the realm of anecdotes. But I think in general when you talk to people in the city, everybody realized 2016 was an awful year, and they know that 2017 was better, and they know that 2018 was better than 2017, so they know things have improved, but gun violence is still far too high. That’s really where I think the danger is: People think, ‘Well, we’ve turned a corner, things have gotten better, I guess we can breathe easy.’ But where Chicago was in 2014 is still way too high.

BF: Some people I’ve spoken to outside of Chicago express the sentiment that the entire city is dangerous. Is that true? Is this violence felt equally across the city?

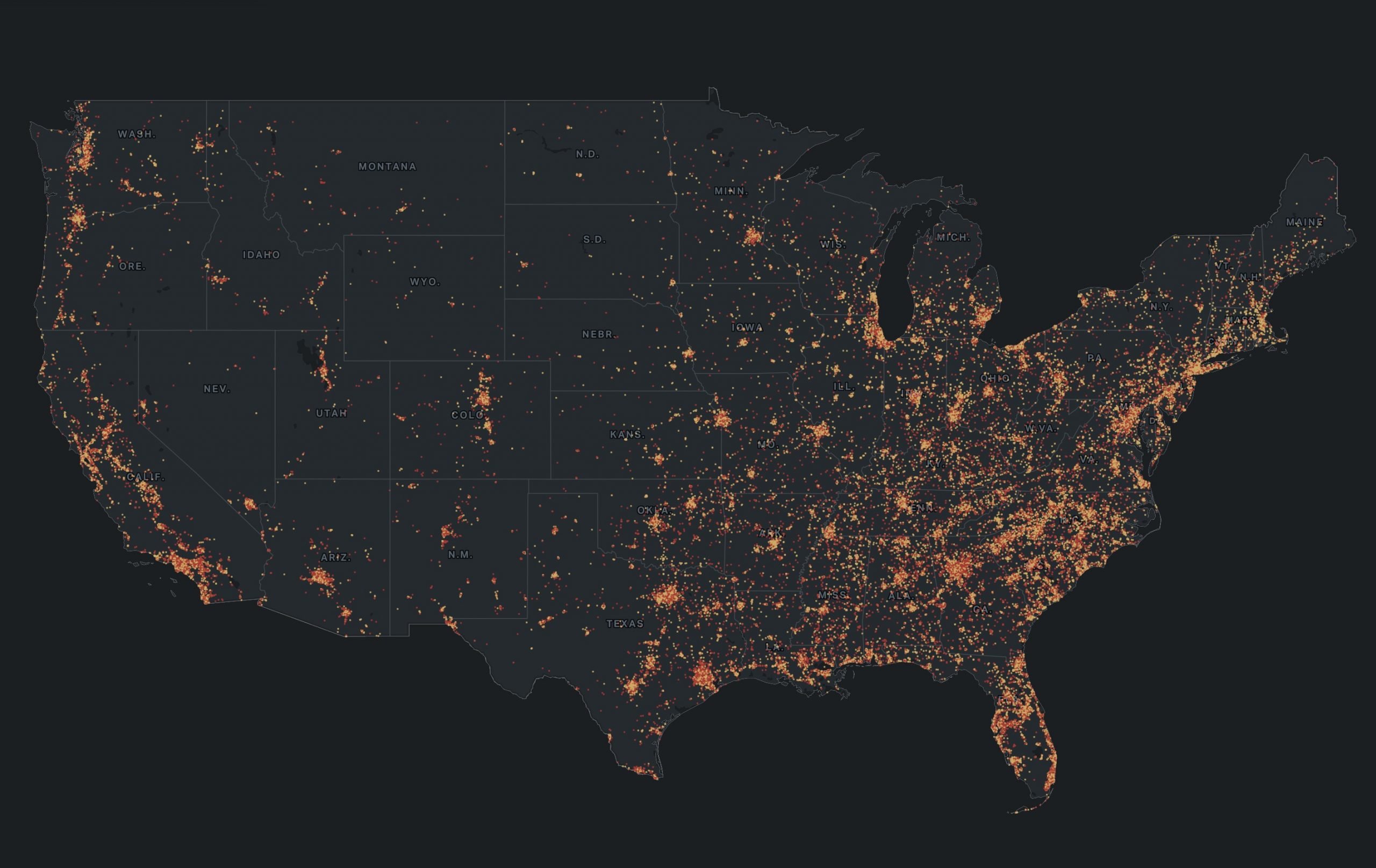

MK: Not at all. It’s so amazingly unequal how the violence is distributed. It is heavily, heavily, heavily concentrated in the South and West Sides, but not just in the South and West Sides, but in specific neighborhoods within those sides, so you can’t even paint with that broad a brush. It’s very, very localized, even to certain blocks in certain neighborhoods.

BF: What are the biggest challenges that the city is facing in bringing about further reductions in gun violence?

MK: While there’s been a lot of progress with the police department, there is still so much work to be done. The clearance rate for homicides is such that only about a quarter of them are being solved, and the rate for nonfatal shootings is in the single digits. I don’t think anybody could possibly look at that and say that the criminal justice system is working in a sense of holding people who commit serious acts of violence to account.

Outside of law enforcement, the state of Illinois is last in how much funding it provides to local school districts, and the reason that’s brought up in this context is because kids who fall off track in their education very often become at very high risk for gun violence.

BF: The Associated Press recently reported that Chicago was on track to recover 10,000 guns this year. There aren’t any gun stores in Chicago. So where are these firearms coming from, and how are they getting onto the streets?

MK: There is no gun store within the city limits, but you can go across the street from the city limits and find gun stores. Some of the guns used in crimes in the city were originally purchased right in Cook County. Illinois’s laws are not so restrictive that it is difficult to purchase a firearm in the suburbs and drive it into the city. Many of the other firearms are purchased in neighboring states such as Indiana and Wisconsin.

The guns get here through multiple routes, but studying this is something that researchers really struggle with because getting data on the original purchase locations of firearms is restricted by federal legislation, and even with that data, you don’t know who purchased the gun on the secondary market. So after that initial purchase, how many times did the gun change hands? How did it get into the hands of someone who used it in a shooting? These are questions we are grappling with.

BF: When the Illinois Legislature convenes next year, are there any anti-violence strategies or policies that lawmakers should have on their minds?

MK: There’s a lot the state can do to help the city of Chicago reduce gun violence. I would focus on education, as I mentioned earlier, but there are other things they could do that might have a more immediate impact. One of the reasons why clearance rates are so low is that witnesses are unwilling to cooperate with law enforcement, unwilling to testify, and that makes it very difficult to bring cases against suspected assailants in these gun crimes. The state could provide better resources to protect those witnesses and help them feel safe.

Another issue they should focus on is the massive backlog at the State Police lab, which Chicago relies on to process certain kinds of evidence. The justice system already works more slowly than anybody would like, and it’s a detriment if these cases languish because we’re waiting for evidence from the lab. If the state wanted to devote more resources to remedying that backlog, it certainly could.